Contents

- What is Hypertrophy?

- Who is Hypertrophy important for?

- How does Hypertrophy happen?

- How to promote Hypertrophy development

- Science behind resistance training for Hypertrophy

- Resistance training programming for Hypertrophy

- Hypertrophy workout examples

- References

- About the Author

What is Hypertrophy?

Firstly, it is important to define hypertrophy. In this blog, hypertrophy will typically refer to muscle hypertrophy, which is the enlargement of muscle mass typically caused by resistance training.

Muscular strength is not to be confused with hypertrophy. Muscular strength is the ability of a muscle or muscle group to exert as much force as possible in a single effort (1). It is often trained using heavy loads for low repetitions. Training for hypertrophy refers to the growth of muscle cells as a result of exercise (1). There will be some crossover between the two, but they ultimately produce different physiological responses, and training programs should reflect these differences.

Who is Hypertrophy important for?

Hypertrophy is often associated with bodybuilding – a sport whereby the size and quality of muscle development determine success, and competitors are judged on their muscle hypertrophy. However, hypertrophy development is valuable to many individuals outside of bodybuilding. Increased muscle mass is beneficial to athletic performance and a necessity for many sports – just look at the physique of sports stars today like Anthony Joshua, Caeleb Dressel, Cristiano Ronaldo, Katie Ledecky, Serena Williams, etc.

Having the optimal level of muscle mass for their chosen sport is a determining factor for success. Apart from sports stars and bodybuilders, many regular exercisers in gyms today are often chasing hypertrophy development. To do so, it is important to understand hypertrophy.

How does muscle growth (Hypertrophy) happen?

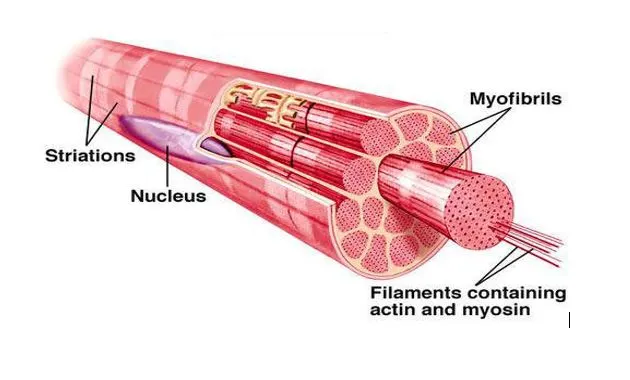

How muscles grow is really a remarkable process. Myofibrils are located within muscle fibres and contain contractile proteins actin and myosin. Amazingly, these myofibrils are so small they would be dwarfed by the diameter of a human hair yet perform such a complex and astonishing operation. Resistance training causes ‘overload’ to the myosin and actin filaments. The body then adapts by repairing and regenerating the myosin and actin, providing correct dietary intake and recovery are provided. As a result of this, the myosin and actin are expanded and enlarged, leading to an increase in the number of myofibrils within a muscle fibre (2). Therefore, muscle fibres (Figure 1) increase in size to accommodate a greater number of myofibrils. This is known as myofibrillar hypertrophy and explains how muscles grow because of resistance training (3).

Hypertrophy is not to be confused with hyperplasia. Hyperplasia is an increase in the number of muscle fibres, whereas hypertrophy is an increase in the muscle fibre area. Although hyperplasia may occur in animals, its role in humans is less clear (5). It appears hyperplasia might occur in humans who have reached their upper limit in size or are using illegal substances to promote growth (1).

How to promote muscle growth (Hypertrophy)?

When looking to promote hypertrophy development, it is important to consider three things; genetics, training, and diet.

Genetics plays a significant role in hypertrophy potential, and someone with poor genetics will consistently struggle with hypertrophy development no matter how hard and thorough they train, compared with someone with good genetics (6). Training programs can be structured to specifically target hypertrophy which will be discussed in greater detail later. Lastly, is diet.

Diet

Diet plays a vital role in hypertrophy. It is well beyond the scope of this blog to delve into the research around hypertrophy and diet, but very general guidelines can be discussed. Primarily, a positive energy balance (consuming more calories than you are expending) is optimal for hypertrophy when combined with resistance training (7). When in a negative energy balance (expending more calories than you are consuming) the anabolic response is reduced and hypertrophy gains are more challenging (6).

Protein appears to be the macronutrient of the highest importance for hypertrophy development – for building muscle, muscle protein synthesis must exceed muscle protein breakdown (8). Schoenfeld (2016) recommends 1.7 to 2 g of protein per kilogram of body weight should be consumed per day (6). Therefore, a person weighing 70 kg aiming to improve hypertrophy should be consuming between 119 to 140 g of protein per day. It is recommended to space the required protein intake throughout the day and research indicates having three to four meals containing a minimum of 25 g of protein consumed every five to six hours is optimal for hypertrophy development (6).

Protein is made up of building blocks called amino acids, some of which are essential and can only be obtained through diet. One of the essential amino acids, leucine (also a branched-chain amino acid), is particularly important to stimulate protein synthesis, and consuming 20-25g of protein which contains 3-4 g of leucine after a workout seems beneficial to kick start protein synthesis (9,10). A general carbohydrate intake of at least 3 g per kilogram of body weight is recommended to provide energy to maximise training performance, but this can vary greatly depending on individual needs and preferences (6).

Science behind resistance training for Hypertrophy

It is important to understand the science that leads to hypertrophy development. Three factors are needed to promote hypertrophy: mechanical tension, muscle damage, and metabolic stress.

Mechanical tension is when muscles produce force to overcome resistance and is considered essential to muscle growth (11). Mechanical tension can be caused by adding resistance to a movement or exercise. Overloading a muscle or muscle group increases mechanical tension, leading to increased muscle mass, while unloading or detraining results in atrophy (muscle loss) (12). Therefore, once a person adapts to a specific weight they are lifting, more load (weight) needs to be placed on the exercise to continue to cause mechanical tension.

Muscle damage occurs following intense resistance training, where the training stimulus leads to damage to muscles (13). This can cause microtears in the sarcolemma, contractile components, or connective tissue (6). After a damaging exercise bout, the inflammatory response of the body is activated to repair and regenerate damaged muscles. Although concentric muscle contractions (shortening) and isometric muscle contractions (tension without motion) can cause muscle damage, eccentric muscle contractions (lengthening) have the greatest impact (6). However, a lot of eccentric training can lead to delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS), resulting in more time needed for recovery and impacting the ability to train regularly.

Metabolic stress is when exercise is used to cause an accumulation of metabolites such as lactate, inorganic phosphate, and hydrogen ions (14). Exercise that relies on anaerobic glycolysis for energy production will produce a build-up of metabolites. It is suggested a greater acidic environment promoted by glycolytic training leads to muscle fibre degradation and therefore causes a hypertrophic response by the body (15). This form of training is very popular among bodybuilders who will spend a lot of time under tension, with moderate to low loads and very short rest periods. An example of this would be performing a workout with 8-12 reps and 3-6 sets per exercise, with only 30-90 seconds rest between sets.

Resistance training programming for Hypertrophy

Unfortunately, there is very little control over genetic makeup. But, resistance training protocol to instigate mechanical tension, muscle damage, and/or metabolic stress can all be manipulated to promote hypertrophic development.

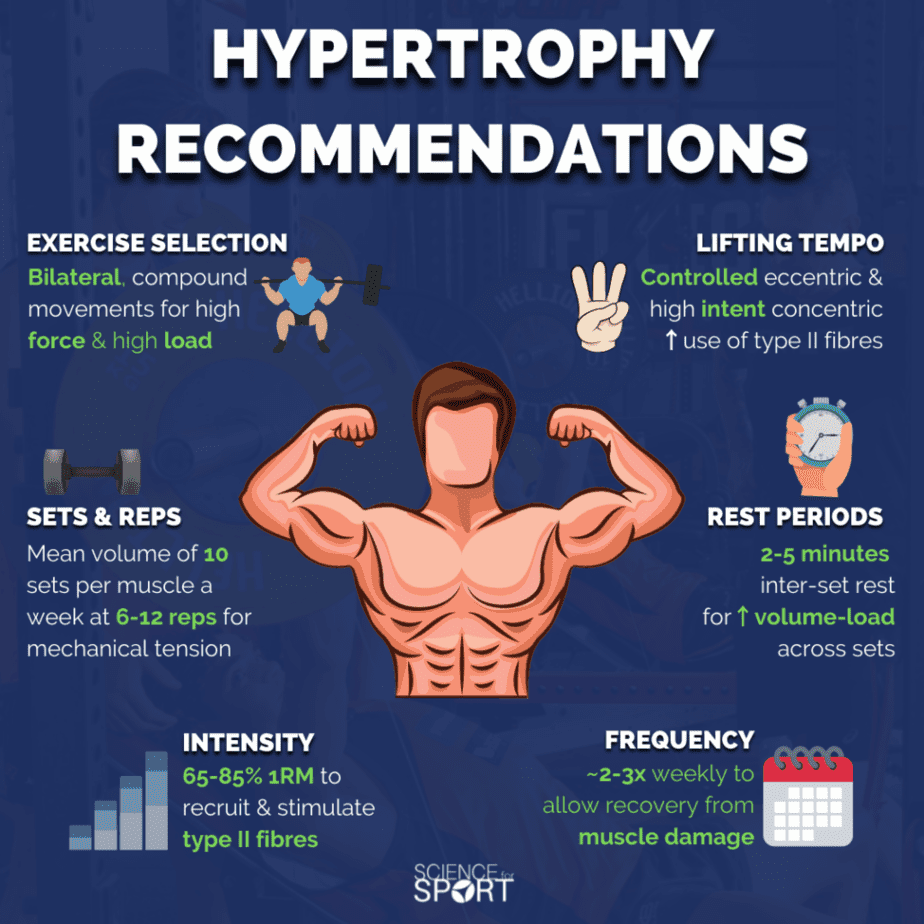

Intensity

The exercise intensity for resistance training is determined by the load lifted and is commonly expressed as a percentage of a person’s one-repetition maximum (1RM). If the maximum a person can squat for one rep is 100 kg, then 100 % of their 1RM would be 100 kg, 75 % of their 1RM would be 75 kg, 50 % of their 1RM would be 50 kg, and so on. Although it is a common thought that the more weight lifted, the ‘bigger’ the person is going to become, it may not be an optimum approach to take. When lifting heavy loads (+ 85 % of 1RM), the number of reps being performed is going to be low, typically six or less. Although substantial mechanical tension will be placed on the muscles, there will not be a considerable enough amount of metabolic stress occurring within them (6). In contrast, lifting very light loads for high repetitions will result in a severe build-up of metabolites, but the forces required to recruit high threshold motor units necessary for hypertrophy will be insufficient (16). Lifting heavy and light loads can both cause hypertrophic responses, but it appears lifting moderate loads (67-85 % of 1RM) will result in the optimal combination of mechanical tension and metabolic stress (1).

Repetitions (reps)

The number of reps a person can perform is directly impacted by the load being lifted. Therefore, a person lifting heavy loads will only be capable of performing a low number of repetitions, and reducing the load will result in more reps being achieved. We know that moderate loads of 67-85 % of 1RM are optimal for hypertrophy, and working with these loads will typically result in 6-12 repetitions being performed. Although there is evidence hypertrophy development can occur across a spectrum of reps, it appears that 6-12 reps results in optimum mechanical tension and metabolic stress promoting hypertrophy (6).

It is common to see some exercisers spending longer in the eccentric portion of the lift (lengthening phase). The idea is, eccentric contractions cause more muscle damage thus leading to hypertrophy. However, according to Schoenfeld (2016) (6), the research on rep speed is not concrete, and using concentric tempos between one to three seconds and eccentric tempos between two to four seconds is an acceptable starting point.

Sets

A set is a group of repetitions performed together before a rest interval is taken. The number of sets performed is directly related to the overall training volume the exerciser will experience. According to the National Strength and Conditioning Association, 3-6 sets of an exercise should be performed if the goal is hypertrophy (1). Volume is essential to hypertrophy and performing 10+ sets per muscle group per week is a solid starting point for those with hypertrophy-oriented goals (15). However, volume can be very individualised, with four sets per muscle group a week being substantial in promoting hypertrophy responses in some individuals (15).

A very common question asked is “Should I go to muscular failure in a set when training for hypertrophy?”. Muscular failure is completing a set until the muscles can no longer produce enough force to complete another rep. Evidence suggests muscular failure promotes hypertrophy development, but it can also lead to potential burnout and overtraining (17,18). Therefore, the use of muscular failure needs to be managed and carefully periodised to ensure its inclusion in programs is beneficial and not negative.

Rest Intervals

The time allowed for recovery between sets and exercises is known as the rest interval. It is generally recommended to allow a 30 to 90-second rest interval for hypertrophy-oriented goals (1). This rest interval will allow for sufficient metabolic stress and promotes the anabolic process associated with increased metabolic stress (2). If the rest interval is less than 30 seconds, it will not allow the individual to regain muscular strength and impair the performance of the next set (6). Long rest times, typically 3-5 minutes, allow full recovery of strength between sets, but metabolic stress is compromised by potentially blunting the hypertrophic response (2).

However, using the general guideline of 30-90 seconds might be problematic when practically applied. Schoenfeld (2016) outlines that hypertrophy is heavily dependent on overall volume load and if the body is not recovered, then performance will be affected in the subsequent sets, and volume cannot be accumulated (6). Therefore, Schoenfeld (2016) suggests rest periods of at least two minutes will promote recovery and allow the completion of scheduled sets ensuring the desired volume is achieved (6).

Exercise selection

Exercise selection needs to be individualised. There is no point in selecting an exercise unless the individual can perform it safely and effectively. For hypertrophy development, both free weights and machine-based exercises can be utilised. Although free-weight exercises provide more activation of stabiliser muscles and transfer greater to sporting settings, machine-based exercises can also promote hypertrophy development for those struggling with poor coordination during free-weight movements (6,19). Machine exercises can help individuals target specific portions of the muscle, which is why many bodybuilders include machine-based exercises in their programs.

Overall, a variety of exercises including free weights and machine-based exercises, as well as single and multi-joint exercises, should be included in a periodised plan for hypertrophy development (6). It is important to work the muscles through their full range of motion to elicit hypertrophic responses (6).

Exercise order

It is very common to see exercise programs scheduling large muscle multi-joint exercises first in a training session before small muscle single-joint exercises. The thought process is that if a single-joint exercise such as a hamstring curl were performed first, it would impair the performance of the hamstrings in a multi-joint exercise such as a deadlift later in the session. Typically, a person will be lifting much more weight when performing a deadlift than a hamstring curl. However, when hypertrophy is the sole goal, it appears exercise order should be selected by lagging body parts. Schoenfeld (2016) outlines that the muscle worked first in a session receives the greatest hypertrophic benefit, and selecting exercise order on the size of the muscle group is not as important (6). Therefore, if an exerciser was hoping to improve muscle development in their biceps, a bicep curl exercise might be better situated at the start of the session.

Hypertrophy Workout Examples

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to hypertrophy training. Training programs need to reflect the goals of the individual, their experience level, access to training equipment, and time they can devote to training. For example, a bodybuilder will typically devote most of their training time to hypertrophy development whereas a sports athlete might only devote one hypertrophy training block each season before emphasising the development of strength, power, and sport-specific training. Although hypertrophy training programs will differ vastly depending on individual needs, the general concepts mentioned earlier should be visible in the program. A quick summary of these concepts is as follows:

- Intensity should be 67-85 % of 1RM

- Rep ranges 6-12 with multiple sets

- Rep tempos should be one to three seconds in the concentric phase and two to four in the eccentric phase

- Rest intervals of 30 seconds to two minutes (sometimes longer if needed)

- Some sets should be done to failure but need to be monitored to avoid overtraining

- A variety of exercises should be performed including single and multi-joint

- Schedule ‘lagging’ body parts at the start of the session

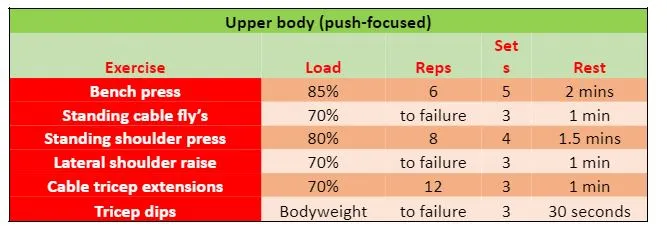

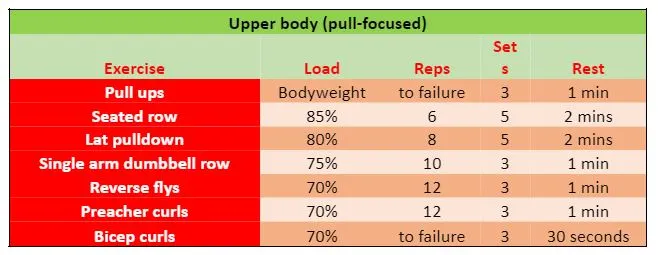

Below is a guide to how a hypertrophy training program can be scheduled. A common ‘push’, ‘pull’, and ‘lower body’ approach is used to ensure all body parts are being exposed to hypertrophy development.

Table 1. Hypertrophy sample upper body (push-focused) workout

Table 2. Hypertrophy sample upper body (pull-focused) workout

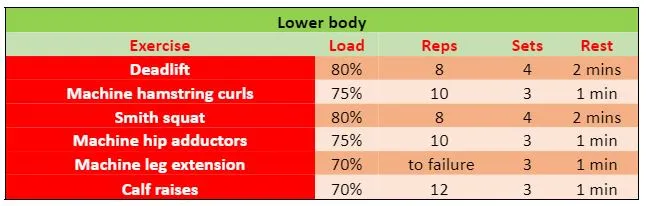

Table 3. Hypertrophy sample for lower body workout

Finally, I hope you can use the principles discussed in this blog to design and implement hypertrophy-oriented training programs to increase muscle size. Don’t forget, learning about hypertrophy and training for hypertrophy both take a lot of time and effort. So be patient with your learning and with your training, and enjoy the process of both!

- Haff, G. G., & Triplett, N. T. (Eds.). (2015). Essentials of strength training and Conditioning 4th edition. Human kinetics.

- Schoenfeld, Brad J. (2010). ‘The Mechanisms of Muscle Hypertrophy and Their Application to Resistance Training’. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(10); pp. 2857-2872.

- Taber, C.B., Vigotsky, A., Nuckols, G., & Haun, C. T. (2019) ‘Exercise-Induced Myofibrillar Hypertrophy is a Contributory Cause of Gains in Muscle Strength’. Sports Med, 49; pp. 993–997.

- Karki, G. (2018). “Muscle-Skeletal Muscle-Gross and Ultra Structure.” Online Biology Notes. [Online] Available at www.onlinebiologynotes.com/muscle-skeletal-muscle-gross-and-ultra-structure/.

- Tamaki, T., Akatsuka, A., Tokunaga, M., Ishige, K., Uchiyama, S., & Shiraishi, T. (1997). ‘Morphological and biochemical evidence of muscle hyperplasia following weight-lifting exercise in rats’. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology, 273(1); pp. C246–C256.

- Schoenfeld, B. (2021). Science and development of muscle hypertrophy. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Churchward-Venne, T. A., Murphy, C. H., Longland, T. M., & Phillips, S. M. (2013). ‘Role of protein and amino acids in promoting lean mass accretion with resistance exercise and attenuating lean mass loss during energy deficit in humans’. Amino acids, 45(2), pp. 231–240.

- Figueiredo V. C. (2019). ‘Revisiting the roles of protein synthesis during skeletal muscle hypertrophy induced by exercise’. American journal of physiology. Regulatory, integrative and comparative physiology, 317(5); pp. R709–R718.

- Garlick P. J. (2005). ‘The role of leucine in the regulation of protein metabolism’. The Journal of nutrition, 135(6 Suppl); pp. 1553S–6S.

- Rondanelli, M., Nichetti, M., Peroni, G., Faliva, M. A., Naso, M., Gasparri, C., Perna, S., Oberto, L., Di Paolo, E., Riva, A., Petrangolini, G., Guerreschi, G., & Tartara, A. (2021). ‘Where to Find Leucine in Food and How to Feed Elderly With Sarcopenia in Order to Counteract Loss of Muscle Mass: Practical Advice’. Frontiers in nutrition, 7; p. 622391.

- Schoenfeld, B. J. (2010). ‘The Mechanisms of Muscle Hypertrophy and Their Application to Resistance Training’. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(10); pp. 2857-2872.

- Goldberg, A. L., Etlinger, J. D., Goldspink, D. F., Jablecki, C. (1975). ‘Mechanism of work-induced hypertrophy of skeletal muscle’. Medicine and Science in Sports. 7(3); pp. 185-198.

- Farthing, J. P., & Chilibeck, P. D. (2003).’ The effects of eccentric and concentric training at different velocities on muscle hypertrophy’. European journal of applied physiology, 89(6); pp. 578–586.

- Smith, R. C., & Rutherford, O. M. (1995). ‘The role of metabolites in strength training. I. A comparison of eccentric and concentric contractions’. European journal of applied physiology and occupational physiology, 71(4); pp. 332–336.

- Schoenfeld, B. & Grgic, J. (2017). ‘Evidence-Based Guidelines for Resistance Training Volume to Maximize Muscle Hypertrophy’. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 40; p. 1.

- Schoenfeld, B. J., Contreras, B., Willardson, J. M., Fontana, F., & Tiryaki-Sonmez, G. (2014). ‘Muscle activation during low- versus high-load resistance training in well-trained men’. European journal of applied physiology, 114(12); pp. 2491–2497.

- Willardson J. M. (2007). ‘The application of training to failure in periodized multiple-set resistance exercise programs’. Journal of strength and conditioning research, 21(2); pp. 628–631.

- Fry, A.C., Kraemer, W.J. (1997) ‘Resistance Exercise Overtraining and Overreaching’. Sports Medicine 23, pp. 106–129.

- Haff, G. G. (2000). ‘Roundtable Discussion: Machines Versus Free Weights’. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 22(6); p. 18.