Contents of Article

- Summary

- Why is measuring balance important?

- What is the Modified Bass Balance Test?

- How do you conduct the Modified Bass Balance Test?

- Is the Modified Bass Balance Test valid and reliable?

- Conclusion

- References

- About the Author

Summary

The original Bass Balance Test is a high-performance balance test that was first presented in 1936 by Dr Ruth Bass [3]. The test has since been modified in 1968 for improved application [4]. Later, in their 1986 book “Practical Measurements for Evaluation in Physical Education”, Johnson and Nelson [5] published the Modified Bass Balance Test as a clinical method for the assessment of functional jump-landing balance performance. Dynamic forward and diagonal movements are coupled with statically maintaining landing positions [4].

Why is measuring balance important?

Balance requires a joint effort from the neuromuscular system and other multi-organ sensory systems (vestibular, visual, and proprioceptive). Balance can be tested both statically and dynamically [1] with no gold standard currently available for the athletic sporting population [6]. Establishing a balance test for this specific population must include dynamic features since all sports require a ‘dynamic’ attribute of balance in some way [6].

The Modified Bass Balance Test used to be the only standardised balance test that incorporates both static and dynamic tasks [4, 5]. Today, balance is often tested on force plates that record the stabilising actions of the foot, but these often remain insensitive to upper-body sway [7].

What is the Modified Bass Balance Test?

As described by Johnson and Leach (1986) [4], the test is performed using both feet in an alternating order to jump to and from tape markers along a course. The distance of the tape markers is fixed and remains the same for every test subject. The tape markers are to be covered entirely with the foot on landing. No additional instructions are given concerning arm and hand placement. No comment on landing and/or technique can be made.

How do you conduct the Modified Bass Balance Test?

All fitness testing should be performed on a dependable surface that is not affected by wet or slippery conditions and is protected from varying weather types. Changes in the testing environment weaken the reliability of repeated tests and result in worthless data.

Required Equipment

- Consistent testing facility (e.g. gym or laboratory)

- Measuring tape

- Marking tape/sports tape

- Metronome (loud audio cues at 60 beats/min)

- Performance Recording Sheet

Test Configuration

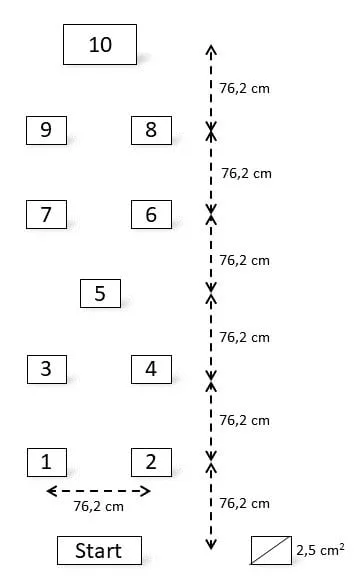

The test is performed with the subject standing on the start marker with their right foot and looking straight ahead. A metronome gives an audio cue every second to ease time orientation for the subject. Instructed to jump to the following marker (marker #1), the subject is allowed to take a brief look at the goal marker, jump, and then land on the ball of the left foot covering the marker.

They must keep their eyes looking straight ahead while maintaining the position for a maximum of five seconds before advancing to marker #2. The five-second stance is counted aloud by the tester to further facilitate time orientation of the subject. All markers are to be jumped to with alternating feet in the numbered order. Figure 1 depicts all distances between the markers.

How do you score the Modified Bass Balance Test?

Each successful landing earns the subject five points. Each second the subject holds a steady position, they are rewarded with another one point; meaning a total of 100 points are possible for the entire test. According to this test, higher scores imply better balance.

Landing faults result in the loss of the five landing points. Landing faults include:

- Touching the floor with the non-supporting foot.

- Touching the floor with the heel of the supporting foot.

- Failing to stop on landing.

The foot partially covering the tape mark results in a three-point loss. Failing the landing entirely, no landing points are being rewarded. The test continues with the subject taking the balance position (ball of one foot on the marker). Holding the balance position for five points can then still give full balance points (0 landing points, 5 balance points; for this marker).

Balance errors include:

- Touching the floor with any other body part than the ball of the supporting foot.

- Moving the planted foot while maintaining balance position.

- If the subject loses balance completely, no additional balance points are rewarded. The subject proceeds by leaping to the next assigned marker. Every balance fault results in a loss of one point per second.

Is the Modified Bass Balance Test valid and reliable?

The Modified Bass Balance Test is a sparsely used balance test. Due to insufficient validation, the test is not recommended in scientific practice.

Ambegaonkar et al. (2013) describe the test as having “…acceptable reliability of 0.75” [2] and a validity of 0.46 [1, 8]. However, since the authors did not go any deeper on this, and the original source from Johnson and Leach (1968) is not available in a computerized version, it remains unclear to which kind of reliability is meant, and if the scientific methods used were sufficient to detect appropriate levels of reliability. Furthermore, the authors were unable to show the differences in balance between dancers and active non-dancers [2].

Tsigili (2001) examined the reliability of the Modified Bass Balance Test by comparing it to the current standard test using a stabilometer, with no significant correlation being observed [8]. Also, the authors recorded very high performance values (mean = 91.45) close to the ceiling of 100 points. This could have impacted variability values. The test seems too easy to perform for their population of undergraduate students [8].

The Modified Bass Balance Test records both static and dynamic movement errors. The end score, on the other hand, combines both scores. It is unclear if static and/or dynamic deficiencies get “washed out” or if the score accurately depicts a person’s balance [1].

As the tape marker distances remain constant and are the same for all participants of the test, it creates an unfair advantage for taller individuals who are less challenged to jump from marker to marker. Therefore, leg length differences make this test difficult for comparison but are not accounted for.

Conclusion

Old tests get replaced by newer, more valid, and quite often, more reliable tests. This is what appears to have happened to the original Bass Balance Test. It got modified, but even this modified version is seldom in use due to obvious disadvantages. One subject gets less taxed throughout the jumping course than another, and the test does not control for arm sway or upper-body balance control actions. Collectively, this reduces the test’s sensitivity and reliability.

As a result, the Modified Bass Balance Test is not recommended in practice where valid and reliable balance results are desired. Check out our article on the “Multiple Single-Leg Hop-Stabilization Test” for a reliable variant of the Modified Bass Balance Test.

- Ambegaonkar, Jatin P.; Caswell, Shane V.; Winchester, Jason B.; Shimokochi, Yohei; Cortes, Nelson; Caswell, Amanda M. (2013): Balance comparisons between female dancers and active nondancers. In Research quarterly for exercise and sport 84 (1), pp. 24–29. DOI: 10.1080/02701367.2013.762287. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=23611005.

- Ambegaonkar, Jatin P.; Redmond, Charles J.; Winter, Christa; Cortes, Nelson; Ambegaonkar, Shruti J.; Thompson, Brian; Guyer, Susan M. (2011): Ankle stabilizers affect agility but not vertical jump or dynamic balance performance. In Foot & ankle specialist 4 (6), pp. 354–360. DOI: 10.1177/1938640011428509. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=22184741.

- Bass, R. I. (1939). An analysis of the components of tests of semicircular canal function and of static and dynamic balance. Research Quarterly. American Association for Health, Physical Education and Recreation, 10(2), 33-52. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10671188.1939.10625750?journalCode=urqe17.

- Johnson, B. L., & Leach, J. (1968). A modification of the Bass Test of Dynamic Balance. Commerce: East Texas State University.

- Johnson, Barry L.; Nelson, Jack K. (1986): Practical measurements for evaluation in physical education. 4th ed. Edina MN.: Burgess Pub. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED048380.

- Riemann, Bryan L.; Guskiewicz, Kevin M.; Shields, Edgar W. (1999): Relationship between Clinical and Forceplate Measures of Postural Stability. In Journal of Sport Rehabilitation 8 (2), pp. 71–82. DOI: 10.1123/jsr.8.2.71. http://journals.humankinetics.com/doi/abs/10.1123/jsr.8.2.71.

- Risberg, M. A.; Ekeland, A. (1994): Assessment of functional tests after anterior cruciate ligament surgery. In The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy 19 (4), pp. 212–217. DOI: 10.2519/jospt.1994.19.4.212. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=8173569.

- Tsigili, N. (2001): Evaluation Of The Specificity Of Selected Dynamic Balance Tests. In Pms 92 (3), P. 827. Doi: 10.2466/Pms.92.3.827-833. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11453210.