Contents of Article

- Summary

- What is peak weight velocity?

- What causes peak weight velocity?

- Why is peak weight velocity important for athletic performance?

- How do you measure peak weight velocity?

- Is peak weight velocity valid and reliable?

- Is future research needed with peak weight velocity?

- How often should you test peak weight velocity?

- Conclusion

- References

- About the Author

Summary

Growth and physical maturation are dynamic processes that encompass a broad spectrum of cellular and somatic changes (1). Growth refers to measurable changes in body composition and various systems within the body, whereas biological maturation refers to significant changes to a number of physiological and structural processes (2). These processes present large inter-individual variation in magnitude, timing and tempo in youth, creating complex and extensive differences in the programming needs of athletes (3).

The transition from childhood to adulthood is known as adolescence and marks the fastest period of growth known as peak height velocity (PHV). However, few studies have acknowledged peak weight velocity (PWV) to the same degree, which marks the maximum rate of increase in weight during the adolescent growth spurt.

Studies of the body size, dimensions, and proportions of athletes have received a lot of attention for many years (4). This information is beneficial for sports scientists and coaches alike, who have recently seen a rise in positions that are created solely for youth athletes (3). Although height in athletes has not appreciably changed on average from the 1970s through to the 2000s, body mass has continued to increase (4).

Recent research has suggested that an advanced understanding and appreciation of training, coupled with improved access to nutritional information and/or calorie intake support this (5). Regardless of existing and current research, it is important that youth practitioners are not only aware of what peak weight velocity (PWV) is but perhaps more importantly, how to programme safely for athletes during accelerated periods of growth (3).

Key terms:

- Youth – The period between childhood and adulthood.

- Growth – Changes in body size, shape and composition.

- Weight – A composite of all bodily tissues, including fat-free mass (FFM) and fat mass (FM)

What is peak weight velocity?

Peak weight velocity (PWV) represents the greatest rate of change in body mass. After peak height velocity (PHV), there exists a time delay (12-14 months, approximately) where there is an increase in body mass compared to stature (6), and it is this period of time that is referred to as PWV. Growth during childhood is a relatively stable process until about the age of four, when girls grow slightly faster than boys (5). This balances out over time as both genders grow at an average rate of 5 to 6 cm/year and 2.5 kg/year until the onset of puberty (5).

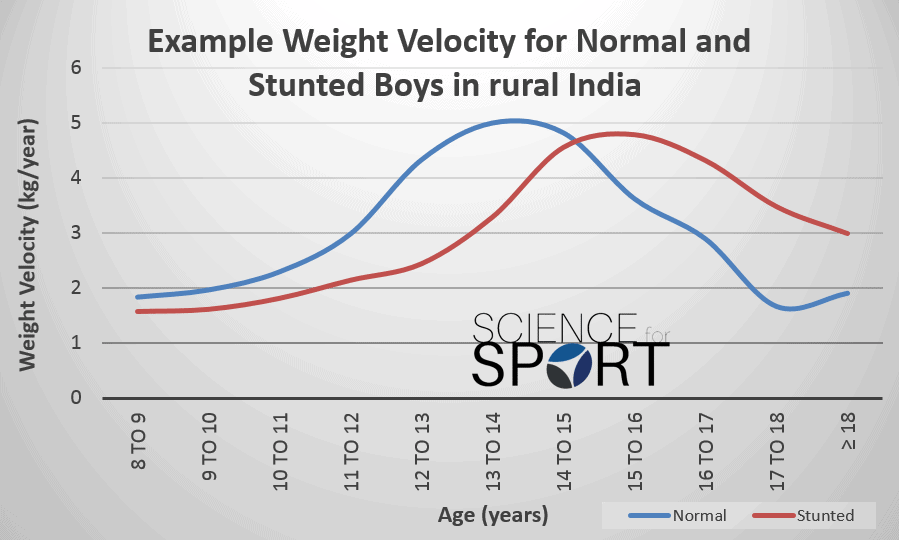

Puberty is also a time of significant weight gain, where 50 % of adult body weight is gained during adolescence. In males, PWV occurs at about the same time as PHV (> 14) and averages 9 kg/year (5). In females, PWV lags behind PHV by approximately six months and reaches 8.3 kg/year at about 12.5 years old. Figure 1 provides a visual example of the weight velocity in rural Indian boys (7). It is important to understand that these data may differ significantly from data collected from children in more developed countries (e.g. UK and Australia) where food access is less restricted and better nutritional education is provided.

Body fat patterning is significantly different between males and females during PWV, with females demonstrating greater trunk skinfold thickness than their male counterparts, who demonstrate larger arm and shoulder girth measures (3). The rate of weight gain for both males and females decelerates during the latter stages of pubertal development (Figure 1) and ends with males’ free fat mass being 25-30 % greater than females, with about half of the overall body fat (3).

What causes peak weight velocity?

Growth is determined by hormones, nutrition and hereditary factors from the athlete’s parents with environmental factors, such as cultural background, socioeconomic status, and physical activity thought to contribute (3). PWV begins with the reactivation of the hypothalamus-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis, which stimulates gonadotrophin-releasing hormones (GnRH) during sleep (12).

This elevated bioavailability of circulating hormones and androgens (testosterone, thyroxine, leptin, parathyroid hormone and growth hormone) (5) develop rapid changes in long bone growth relative to muscular lengthening that may disrupt structure, neuromuscular function and physical performance (3). Whilst excessive weight gain during childhood is linked to several health issues such as obesity, asthma and early onset arthritis (8), PWV may be considered the ‘normal’ alteration in mass that marks the transition between childhood and adulthood.

Why is peak weight velocity important for athletic performance?

Physical performance is commonly measured as the outcome of motor tasks requiring speed, agility, strength, and power (3, 9). However, the rapid increases in body dimensions and muscle hypertrophy during adolescence suggest that movement proficiency may be affected as athletes negotiate with fluctuating levels of coordination (i.e. the sudden increase in body size is likely to affect coordination) (10).

As a result of the physical changes that accompany adolescence, both males and females may struggle to perform simple motor tasks such as balancing, running, and change of direction task (1). Coaches must be mindful of this and allow athletes to develop new strategies and solutions in essentially a ‘new’ body (10).

Without muscle hypertrophy, high-force activities such as landing, change of direction tasks or heavy strength training could predispose children to poor force-attenuating capabilities, limit physical performance, and increase the relative risk of injury (3). However, alterations in bone mineral content, muscle size and tendon strength will occur as a result of PWV, which inevitably leads to an increase in muscle strength, power, reactive strength index and stretch-shortening cycle function over time (3).

Like PHV, exercise programmes must be monitored and supervised by a qualified practitioner during PWV to ensure that health and safety are maintained. This is more important with a vulnerable population, where the coach, scientist, or teacher has legal, ethical, and moral responsibility for maintaining and promoting well-being (3).

How do you measure peak weight velocity?

Monitoring PWV is an active intervention that should be conducted approximately every six months to ensure that this phase is not missed (3). This can be achieved by plotting the athlete’s mass on a simple Excel template over time, or dividing mass by time (e.g. kilograms per year (kg/yr)) to produce a comparable output.

Some practitioners prefer to monitor PWV more frequently (e.g. every 3-4 months), so as to not miss this stage of development. PWV measures are similar to PHV, but must be plotted after PHV to ensure that mass is continually tracked after PHV in both males and females.

Is peak weight velocity valid and reliable?

Measurements of mass are limited by some methods due to human error. For example, skinfold measures have been shown to have high intra- and inter-observer reliability, which is made more difficult when there is high subject variability, such as high levels of adipose tissue (11). Similar arguments are made with waist-circumference measures, where a lot of the results are predictive in nature, which limits the statistical significance of the test (11).

For truly accurate measures of mass, Bioelectric Impendence analysis (BIA) and Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scans are the ‘gold standard’, but these can pose high financial cost, travel arrangements, and are somewhat invasive in a youth sample (3,11). Alternatively, measurements on a reliable set of scales, taken at approximately the same time have proven to produce an accurate measure of the onset of PWV.

Is future research needed with peak weight velocity?

Future research should look to observe and report PWV to the same standards that PHV has been described and interpreted by paediatricians and sports scientists. Moreover, future research should look to investigate:

- What reliable, non-invasive, and financially accessible measures are there to measure PWV?

- How does PWV affect physical performance in both males and females during the process?

- How can practitioners alter training and potentially dietary needs during PWV to maintain health and safety?

How often should you test peak weight velocity?

Measures of weight should be taken roughly 2-3 times a year due to the magnitude and timing of PWV, which is different per subject. An athlete of the same chronological age can be separated by as much as five years of biological development (3), which must be considered when collecting measurements. Therefore, monitoring weight, height, and cognitive function may provide a holistic view of the athlete at hand, allowing for a more individually tailored exercise regime.

Conclusion

The relative paucity of research makes PWV a seemingly misunderstood phenomenon, which limits our true understanding of how youth athletes need to be programmed during this period. Nevertheless, current recommendations are aligned with those of PHV, which suggests that a suitable loading regime coupled with adequate supervision in sessions is safe and effective during PWV (3).

- Manna, I., 2014. Growth Development and Maturity in Children and Adolescent: Relation to Sports and Physical Activity. American Journal of Sports Science and Medicine, 2(5A), pp.48-50. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Indranil_Manna/publication/267453319_Growth_Development_and_Maturity_in_Children_and_Adolescent_Relation_to_Sports_and_Physical_Activity/links/545055800cf249aa53da90f3.pdf

- Moran, J., Sandercock, G.R., Ramírez-Campillo, R., Meylan, C., Collison, J. and Parry, D.A., 2017. A meta-analysis of maturation-related variation in adolescent boy athletes’ adaptations to short-term resistance training.Journal of Sports Sciences, 35(11), pp.1041-1051. http://shapeamerica.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02640414.2016.1209306

- Lloyd, R.S., Cronin, J.B., Faigenbaum, A.D., Haff, G.G., Howard, R., Kraemer, W.J., Micheli, L.J., Myer, G.D. and Oliver, J.L., 2016. National Strength and Conditioning Association position statement on long-term athletic development. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 30(6), pp.1491-1509. http://www.igotrypt.com/files/The_National_Strength_And_Conditioning_Association96550.pdf

- Malina, R.M. and Figueiredo, A.J., 2017. Body Size of Male Youth Soccer Players: 1978-2015. Sports medicine (Auckland, NZ). https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40279-017-0743-x

- Rogol, A.D., Roemmich, J.N. and Clark, P.A., 2002. Growth at puberty. Journal of adolescent health, 31(6), pp.192-200.https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/12c9/dbe5abb571253be423e3cc5522632351bc57.pdf

- Fort-Vanmeerhaeghe, A., Montalvo, A., Latinjak, A. and Unnithan, V., 2016. Physical characteristics of elite adolescent female basketball players and their relationship to match performance. Journal of human kinetics, 53(1), pp.167-178. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5260586/

- Kanade AN, Joshi SB and Rao S. undernutrition and adolescent growth among rural indian boys. Indian Pediatrics 1999; 36:145-156. http://indianpediatrics.net/feb1999/feb-145-156.htm.

- Marinkovic, T., Toemen, L., Kruithof, C.J., Reiss, I., van Osch-Gevers, L., Hofman, A., Franco, O.H. and Jaddoe, V.W., 2017. Early infant growth velocity patterns and cardiovascular and metabolic outcomes in childhood. The Journal of Pediatrics. http://www.jpeds.com/article/S0022-3476(17)30189-0/fulltext

- Schulz, K.M. and Sisk, C.L., 2016. The organizing actions of adolescent gonadal steroid hormones on brain and behavioral development. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 70, pp.148-158. http://s3.amazonaws.com/academia.edu.documents/50868193/Schulz_and_Sisk_2016.pdf?AWSAccessKeyId=AKIAIWOWYYGZ2Y53UL3A&Expires=1499597462&Signature=na75zf8ISNy0vlmns3RznLL773Q%3D&response-content-disposition=inline%3B%20filename%3DThe_organizing_actions_of_adolescent_gon.pdf

- Chow, J.Y., Davids, K., Button, C. and Renshaw, I., 2015. Nonlinear pedagogy in skill acquisition: An introduction. Routledge. https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=x8U0CwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=Nonlinear+pedagogy+in+skill+acquisition:+An+introduction.+Routledge.&ots=8ZvF0Qcg7j&sig=OXIFQiw3LCiYoR6PY5Ofg6xOr2g#v=onepage&q=Nonlinear%20pedagogy%20in%20skill%20acquisition%3A%20An%20introduction.%20Routledge.&f=false

- Wells, J.C.K. and Fewtrell, M.S., 2006. Measuring body composition.Archives of disease in childhood, 91(7), pp.612-617. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2082845/

- Peper, J.S. and Dahl, R.E., 2013. The teenage brain: Surging hormones—brain-behavior interactions during puberty.Current directions in psychological science, 22(2), pp.134-139. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4539143/